Middle School Heart Lessons: From Pulse Rates to Dissection

Does teaching middle heart lessons seem dull and boring to your students, especially with all of the vocabulary involved? It doesn’t have to just be diagrams and labels.

Middle School Heart Lessons: From Pulse Rates to Dissection

April 2025

I like to hook the student’s interest by looking at the hearts of other animals, doing labs to measure pulse rates, playing a board game, and then doing a very cool sheep heart dissection!

How Are Animal Hearts Different?

Instead of jumping straight into teaching about the human heart, I like to start by comparing hearts across the animal kingdom. It grabs the students attention and gets them interested in what their own heart looks like.

Did you know that an octopus and squid have three hearts? One pumps to the body, and the other two pump to the gills. Even weirder is that when the octopus swims, the one that pumps to the body stops beating! That’s why you often see octopuses crawling along the bottom of the ocean.

Earthworms don’t really have a heart, but they have five aortic arches that act like hearts.

Fish only have a two-chambered heart instead of the four chambers that we have.

Amphibians such as frogs and salamanders have a three-chambered heart with two atria and one ventricle.

A giraffe’s heart can weigh up to 25 pounds to pump blood all the way up to the brain!

The blue whale has the largest heart in the world and it can weigh up to 400 pounds. It is the size of a small car!

Insects don’t really have hearts either. Instead, they have long tube-like structures that pump a blood-like substance throughout their body.

Why Is The Heart So Important?

Now it’s time to focus on the human heart and its basic jobs. Emphasize that it’s just a pump. A common misconception is that the heart gives oxygen to the blood, which isn’t the case. What it does do is pump blood all the way down to the toes, and up to the brain, to deliver oxygen and nutrients to all the body’s cells. It also removes the toxic waste gas, called carbon dioxide, from our cells.

A very important part of the heart is that it never gets tired, even though it pumps over 100,000 times a day! I do an activity where students raise one hand above their head and open and close their fist for as long as they can. Usually, within a minute or two, they start feeling pain in their arms and chest. Eventually, they can’t keep going. This is a great way to compare skeletal muscles, which do get tired, with cardiac muscle, which doesn’t.

Finding Our Pulses

This is a good time for students to measure their pulse. It may take a few moments to find it, especially if they are at rest. I ask them to take two fingers, go in front of their ear, slide down under their jaw, and push in gently. They should be able to feel their pulse in their neck. I have them count the beats for ten seconds which they then multiply by six to get the beats per minute reading.

They then do jumping jacks or run up and down the steps to get their rates up. After exercise, it is much easier to find their pulses. They count the beats after two minutes and then after five minutes. This leads to good discussions about why the pulse rate increases with exercise and then the importance of the recovery period.

Teaching the Pathway of Blood Through the Heart

Before we ever dissect, students need to understand the flow of blood through the heart and lungs. I’ve always used the phrase: “Right, right, lungs. Left, left, out.” I tell them that if they remember that, they’ll remember most of the blood flow.

What does this mean?

Right atrium to right ventricle to the lungs, then left atrium to left ventricle and out to the body through the aorta. I even see students write this at the top of their quizzes to help them remember.

I give them a blank drawing of the heart and have them color the areas that carry red (oxygenated) blood and blue (deoxygenated) blood. This gives them a visual of how the oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood moves.

We start with the superior and inferior vena cava, which bring deoxygenated blood from the body into the right atrium.

The tricuspid valve opens and lets the blood flow into the right ventricle. The right ventricle squeezes and pushes the blood through the pulmonary valve into the pulmonary artery on its way to the lungs.

In the lungs, carbon dioxide is exchanged for oxygen at the capillary level and the blood turns red. The pulmonary veins bring this freshly oxygenated blood back to the heart into the left atrium.

The blood flows through the bicuspid (or mitral) valve into the left ventricle. I always emphasize that the left ventricle is the strongest chamber because it needs to push blood all the way down to the toes and up to the head. Students will see this during the dissection.

The left ventricle pushes the blood through the aortic valve into the aorta, which branches off to the brain, arms, and then down behind the heart to the lower body.

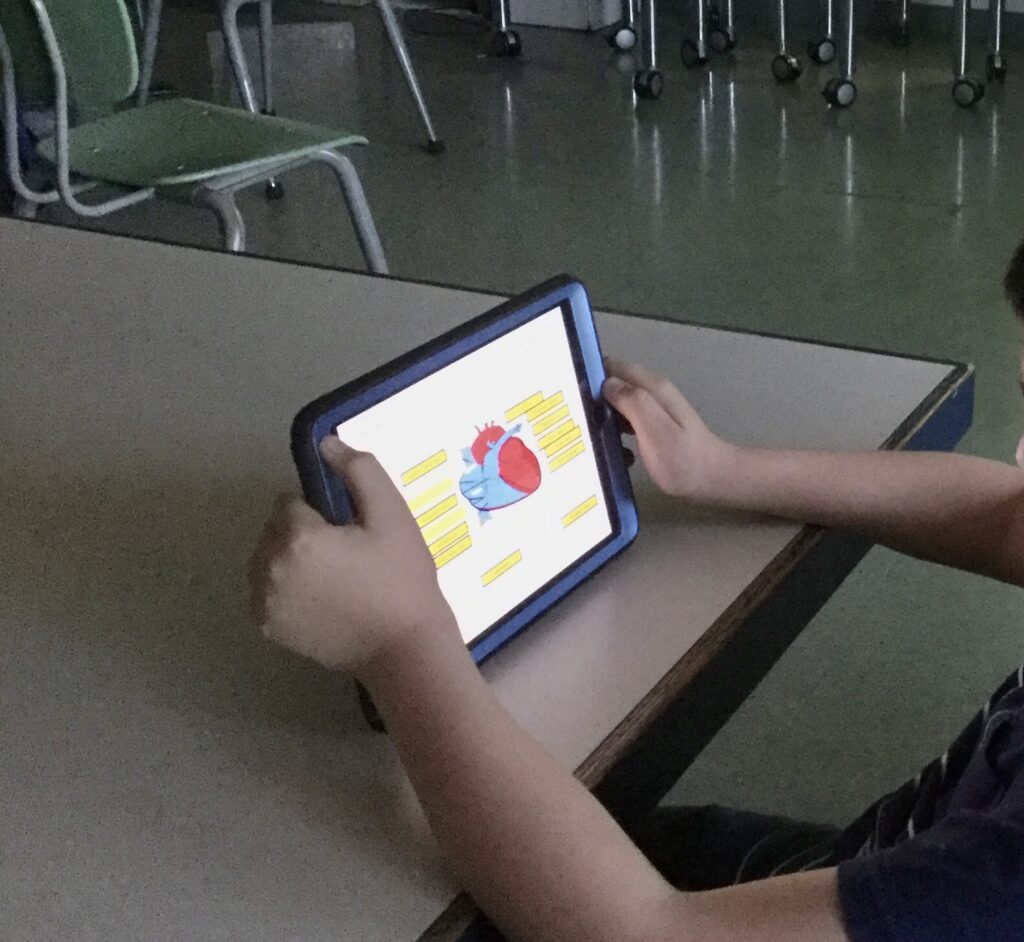

After labeling the heart diagram, students do a drag-and-drop digital activity to reinforce structure names.

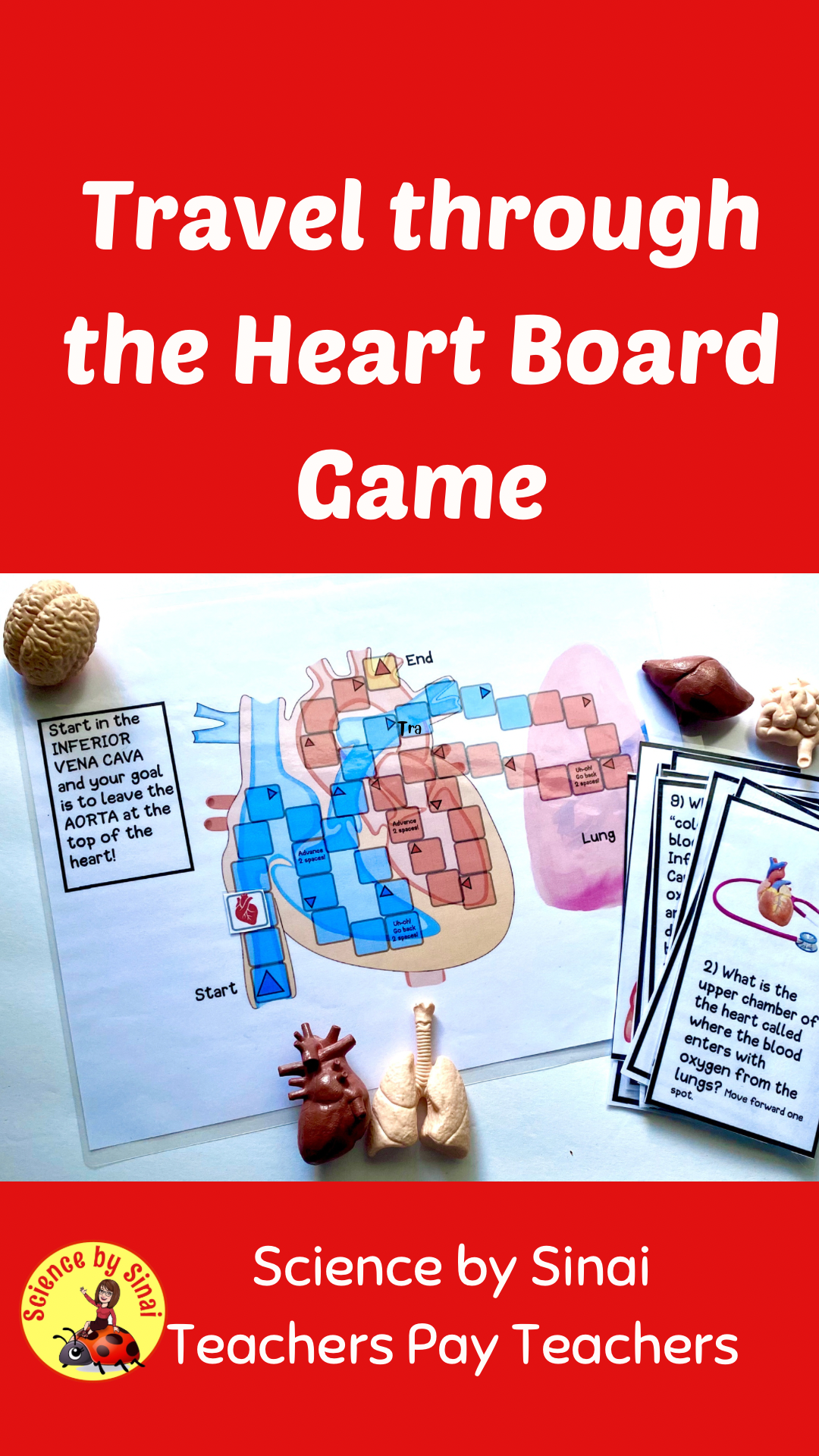

I always give a quiz before dissection so students understand what they’re seeing. To prepare for the quiz, we use a heart blood pathway board game. Students move from the vena cava through to the aorta by answering review questions to advance or go back.

I am a big fan of using games for review on just about any subject. Please check out this blog post called Review Made Fun: Science Classroom Gamification.

Dissecting Sheep Hearts

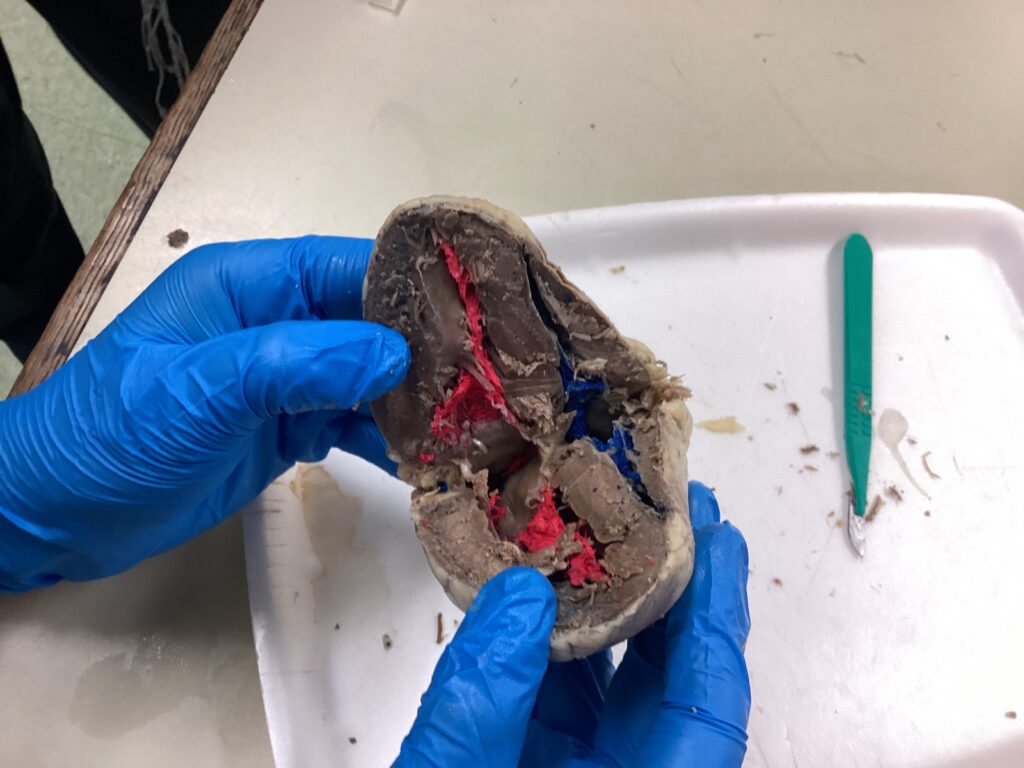

By the time we get to the sheep heart dissection, students are well prepared. They understand the structures, flow, and vocabulary.

For the squeamish, I remind them this is probably a once in a lifetime opportunity. Unless they go to medical school, most people will never hold a real heart in their hands again. In the end, even the most hesitant students are fascinated. On the contrary, they are often the ones poking around the most!

I assign partners the day before and go over safety and handling procedures thoroughly. We use goggles, gloves, dissection trays, and I give plenty of warnings about the sharpness of scalpels.

We carefully cut around the apex of the heart but not all the way through. Leaving the upper part intact helps tremendously with orientation. Cutting all the way through can damage the aorta, pulmonary arteries, and veins. I like students to use gloved fingers or old pencils to poke into the vessels of the heart.

While the valves usually get cut during dissection, students can still see the string-like chordae tendineae that help open and close the valves.

Once the heart is open, students work with their partners to identify structures using prior knowledge. Their goal is to pass a mini practicum quiz with me where they bring their heart over and answer questions like, “Show me the aorta,” “Where does blood go after the right ventricle?” or “Where is the mitral valve?”.

Teaching About Blood and Blood Types

Learning about the heart isn’t complete without understanding blood, so we get into what blood is made of.

We cover the four main components: red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, and plasma. We also review the four major blood types: A, B, AB, and O. I encourage students to find out their own blood type which makes learning about compatibility more interesting.

Teaching the heart doesn’t have to be dry or overwhelming. It can actually be one of the most exiting parts of your science year.

If you would like more ready-to-use anatomy lessons, that are easy to teach and fun for students, please take a look at my anatomy resources in my Science by Sinai store on Teachers Pay Teachers.